Your Support Makes A Difference

At its core, history is a collection of stories of people doing ordinary and extraordinary things that have a profound impact on the world we see today. Donate now to help us tell Charlotte's stories.

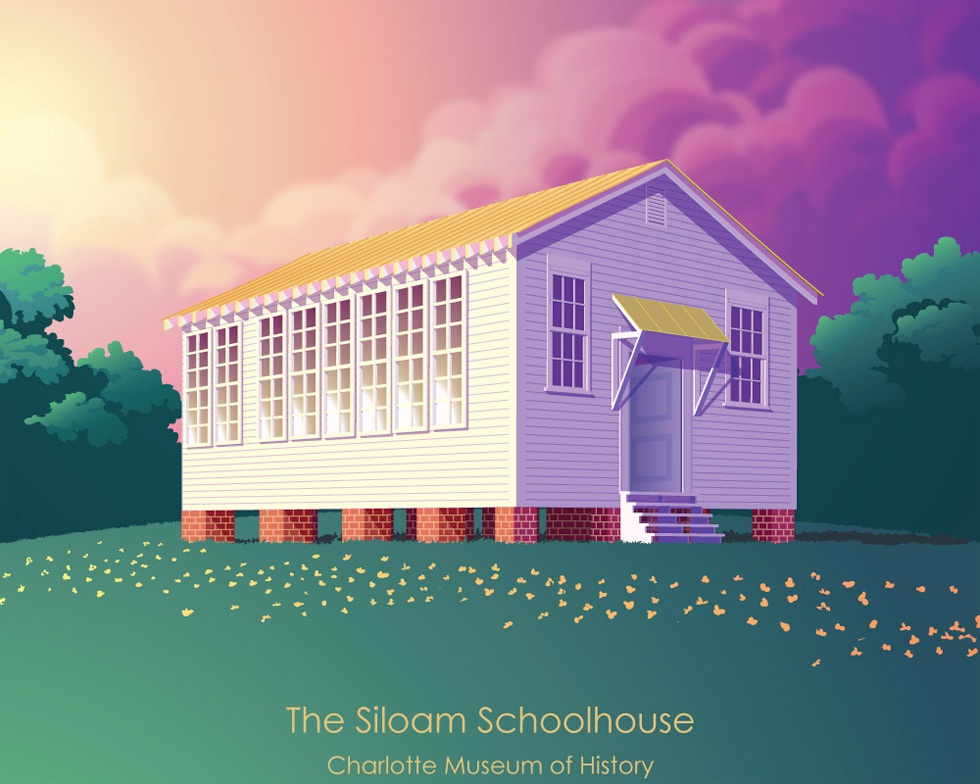

The

historic Siloam School is one of Mecklenburg County's oldest remaining African

American schoolhouses, and one of our community's last standing Rosenwald-era

Schools. On the National Register of Historic Places, the school is endangered

due to its current state of disrepair. Before the Save Siloam School Project,

the building and its stories were at risk of being lost to time.

On November 1, 2022 the Save Siloam School Project exceeded its fundraising goal thanks to generous support from across the community—raising $1.2 million to save and restore this important piece of Charlotte history!

On September 8, 2023 the Siloam School moved to its new home on the eight-acre campus of the Charlotte Museum of History in east Charlotte. Once restored, the space will become a community resource and a center for history education, including exhibits about the 20th-century Black experience and the region’s history of racial discrimination and injustice. The Siloam School will be the only Rosenwald-designed school in Mecklenburg County devoted to history programming.

On June 15, 2024, the Siloam School opened to the public for the first time in decades! The newest addition to the Charlotte Museum of History campus will be open to visitors each day between 1-2pm, or for special group tours with advanced notice.

At its core, history is a collection of stories of people doing ordinary and extraordinary things that have a profound impact on the world we see today. Donate now to help us tell Charlotte's stories.

Siloam School was built around 1920 to replace an earlier school that was most likely a log structure. Like most of the Black schools of the time, the school was built by the community, utilizing their talents as carpenters and tradesmen. The school was named after Siloam Presbyterian Church, located just north of the school, and served the Black students who lived in the rural Mallard Creek neighborhood.

Though Siloam School was built by members of the community, the county school system provided and paid a salary to the instructor and janitor/caretaker and the students were registered in the county school system. County records for the 1924-25 school year indicate there were 72 Black children living in the Siloam district, but only 63 were registered at the school. Average daily attendance was 39 students that year. In other years, between 40-60 students were registered at the school, with the average daily attendance falling somewhere between 20 and more than 30 each day.

Two of the teachers, Margaret Gilliard (1922-23) and Mattie Osborne (1923-25), lived in Charlotte and commuted to Siloam by bus and by foot each day. Ms. Gilliard traveled from Ward 1 on N Caldwell St, a journey of more than ten miles. Mrs. Osborne lived closer, just south of what is now UNC Charlotte. One of the janitors, Nelson Young walked five miles from his home to the school to light the coal stove and get water from the nearby spring before students arrived each day. His son, James, attended the school as a child in the 1930s while his father worked there.

As the school system expanded, one-room schools like Siloam were gradually replaced with new buildings that separated grades. At some point prior to 1947, Siloam School ceased operations and the students moved to different schools in North Charlotte and the county began looking for a buyer for the property. The Young family, who had attended and cared for the structure since the 1930s, bought the school in 1951, led by their father James Young.

The Young family converted the structure into a home for their family, then later an auto garage. After the 1980s, the structure was no longer used by the family. In the early 2000s, the property was purchased by a developer and turned into a sprawling apartment complex which now looms over the one-room school.

Learn more about the school and see the pre-restoration structure by reading the digital guidebook linked below.

In the early 20th century, educators at the Tuskegee Institute, led by Dr. Booker T. Washington, conceived of a program to build high-quality, free primary schools for Black children throughout the segregated rural South. Washington enlisted the aid of Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., to finance the effort, which led to the creation of the Julius Rosenwald Fund in 1917

The program offered matching funds, detailed architectural plans, and fundraising support to communities that wanted to build schools for Black students. By 1928, a full one-third of the South’s rural Black students and teachers were served by Rosenwald Schools. In all, the Fund facilitated the construction of more than 5,000 schools in the South – 813 of them in North Carolina and 26 in Mecklenburg County, the most of any county in the US.

The Rosenwald School designs could be requested by anyone, not just communities that used Rosenwald Funding. They proved to be so popular that the Fund published all of their designs, with clear instructions for paint color, lot selection, and even window treatments in a pamphlet in 1924.

The Rosenwald Fund did not contribute to the building of Siloam School, but it was built according to Rosenwald plans. Based on the 1-A plan, the building accommodates one teacher and was designed to have a central classroom with an industrial space in the rear and two cloakrooms in the front. The door faces North and the building originally had three large windows on each side, to allow for as much light since the school did not have electricity.

To learn more about Rosenwald Schools in Mecklenburg County, visit HistorySouth.org.

The effort to save the Siloam School began in earnest in 2016 when the Charlotte Museum of History agreed to lead a community project to save the historic school in Northeast Charlotte. This came after discussions with two groups that were advocating to save the space—the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission and Silver Star Community Inc., a grassroots nonprofit based in Matthews that has been working to save Rosenwald Schools and Black spaces in Mecklenburg County for more than 10 years. Silver Star was the original champion to save Siloam School.

A dedicated committee of partners and volunteers has worked to save and restore the historic structure since the project formed in 2016, including the Charlotte Museum of History, Mecklenburg County, the City of Charlotte, the Historic Landmarks Commission, Aldersgate Retirement Community, Silver Star Community Inc., Tribute Companies, and a growing number of other community organizations and individuals listed below.

Together with our community partners, the Museum developed a detailed plan for relocating the Siloam School, stabilizing the structure, and finding new uses for it.

Based on extensive community input, the museum uses the structure as a teaching resource, a window into aspects of life for rural African American families in Mecklenburg County in the early 20th-century – and a prism through which we can better view issues of social justice in the 21st-century.

We've seen incredible commitments from public partners and private contributions, including commitments from The Gambrell Foundation, Mecklenburg County, Lowes, Tribute Companies, Sandra Wilcox Conway, the City of Charlotte, Porter Durham, Bank of America, Hoffman Mechanical, and Walmart. Initial Fundraising for the project raised $1.2 million to save and restore the school. Ongoing funding will remain crucial to emmeshing the school in the broader programming of the Museum. Continued donations remain most welcomed.

Save Siloam School Project Champions serve as critical community ambassadors of the Save Siloam School Project. Champions share their talents by sharing their professional expertise, diverse knowledge of constituent perspectives, connections to local, state, or national resources, colleagues or peers, and their philanthropic support.

Project Champions: Kobi Brinson, Commissioner George Dunlap, Maxine Eaves, Councilman Larken Egleston, Anthony Foxx, Valaida Fullwood, Harvey Gantt, Arthur Griffin, Susan Harden, John Howard, Commissioner Mark Jerrell, Mayor Vi Lyles, Darrel Williams, Councilman Greg Phipps, Sandra Wilcox Conway, Dr. Rochelle Brandon, and Dr. Peggy Fuller.

Fannie Flono (chair), Fred Alexander, Lu-Ann Barry (SpiceLAB Media), Everett Blackmon (Winning Images! Photography), Dr. Rochelle Brandon, Janet Brooks, Jeanie Cottingham, Dee Dixon (Pride Communications), Shayvonne Dudley, Commissioner George Dunlap, Dr. Hugh Dussek, Maxine Eaves, Jett Edwards, Councilman Larken Egleston, Dr. Peggy Fuller, Stewart Gray, Belinda Grier, Dr. Tom Hanchett, Susan Harden, Boris Henderson (Aldersgate), Jerry Hollis, John Howard, Angel Johnston, Shirell Joyner, John Kincheloe, Tiffani Lewis, Ting Li (Pixelatoms), Dan Morrill, Mary Newsom, Len Norman, Councilman Greg Phipps, Eric Ridler, Tracy Ryals, Michael Solender, Queen Thompson, Brigette Tinsley, Tiffany Walker, Lauren Wallace, Peter Wasmer, and Tony Womble.

Mark S. Tully (Project Manager, WestEnd Consulting), John Kincheloe (Architect, LS3P), Samantha Brennan (Architectural Intern, LS3P), Jason Dolan (Engineer, Timmons Engineering), Kent Tanner and Korey Jefferson (Tribute Properties), Griffin Masonry, Showalter Construction, Dale Ballew (Reclaimed Lumber and Beams, LLC.), Radco Roofing and Copper Works, and Mickey Simmons (Simmons House Moving).

A special thank you to the Department of Anthropology's 2023 Summer Field School at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte for completing an archaeological survey of the site.